Doosan Bobcat T7X

(All images courtesy of Bobcat)

Construction’s wildcat

Doosan Bobcat is using electrification to not only reduce emissions in construction but also radically change the operation of compact track loaders, reports Will Gray

Construction is not the first industry you think of when it comes to sustainability or electrification. Heavy, power-hungry machines do not immediately suggest the ideal platform for battery-powered performance, yet Bobcat has discovered the opposite, with its new T7X compact track loader outperforming its diesel-powered equivalent in almost every area.

Bobcat began developing the T7X in 2018, when innovations in the EV industry began to point towards potential crossovers. It identified compact track loaders as ideal candidates for electrification, being the most common and most purchased machines in compact construction.

Joel Honeyman, vice-president of global innovation at Bobcat, recalls: “Electrification was starting to become more prevalent in the automotive world and our customers were wanting to reduce their carbon footprint, noise, vibration and other environmental considerations, so they started asking us about those types of solutions.

“It just made sense for us to start with the heart of the line-up because we didn’t want this to be a niche type of product. Automotive had started before our efforts and there was already a lot of components, but not so much in our core industry, so we took the opportunity to take all of these emerging technologies, adapt them and combine them altogether.

“The easy thing would have been to just take the diesel engine out, put a battery into our current products and have an electrified product, but because of the new technologies available, and the opportunities they presented, it allowed us to think about electrification in a different way.”

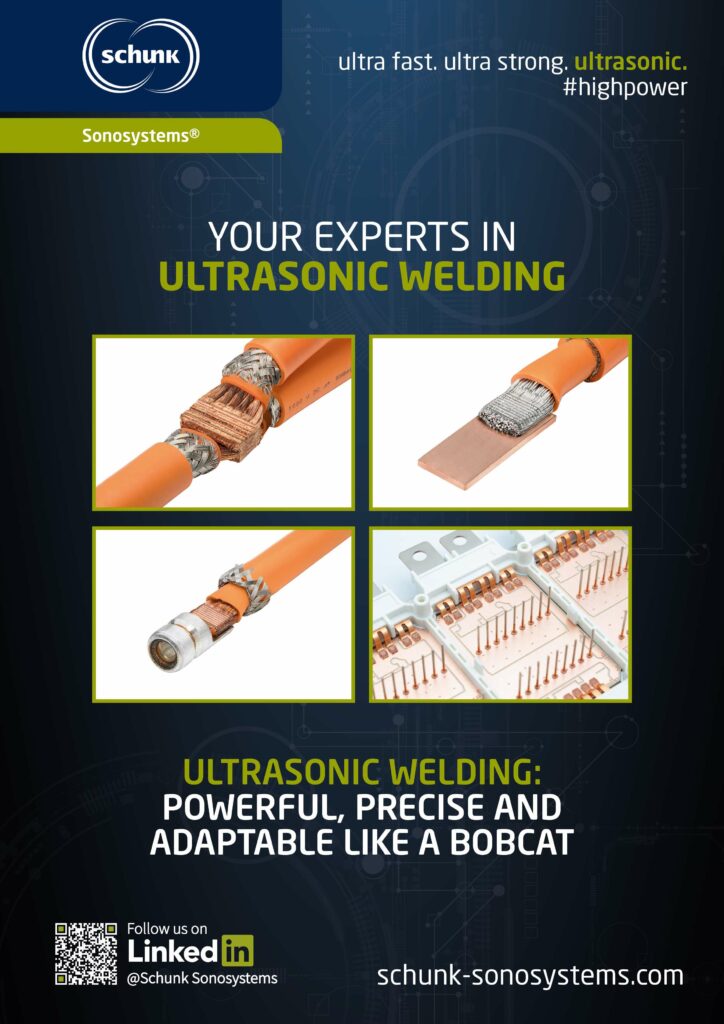

That innovative approach has led to the creation of an all-electric solution that not only eliminates the diesel engine but also replaces the entire hydraulics system, which is used to move the lift arm and tilt functions, and for the auxiliaries that control the various available attachments. This has completely revolutionised the machine.

John Pfaff, director of innovation engineering at Bobcat, describes the new machine as having similar characteristics to “a robot”, and in some ways it has comparisons with a modern, fly-by-wire fighter jet in that it remains manually operated while being managed by highly intelligent software that constantly balances and optimises power and performance.

Total electrification

The standard, compact track loaders in Bobcat’s range are typical of those found throughout the industry. They are the Swiss Army Knife of compact construction, with high-power inline diesel engines, hydrostatic drive systems, a hydraulic power workgroup and auxiliaries used to operate a huge variety of tools that can be fitted to the carrier’s attachment interface.

These machines are workhorses that perform a whole range of tasks using attachments that can include box blades, combination buckets, rotary cutters, dumping hoppers, graders, pallet forks, planers, rotary grinders, scarifiers, scrapers, snow pushers, spreaders, tillers, tree transplanters, vibratory rollers and wood chippers.

That list alone demonstrates the versatility that is required and indicates that perhaps those initial thoughts of these machines being the most suitable for electrification could have been wide off the mark. However, early on in the development phase it became clear to the team that nothing could have been better suited.

“These are not cars; these are used by people to move materials and run lots of different attachments,” says Honeyman. “They need maximum power and performance, and we quickly discovered that the technology that had been developed could allow us to optimise the machine’s performance further from those standpoints.

“Hydraulics have been around for 80 or 90 years and are very well-refined, but, like other technologies, they have their limitations. As we started to think about the whole platform, our engineers began to think about how, instead of just taking the engine out and putting a battery in, perhaps we could make this an all-electric platform.

“We explored many options, looking to advancements in other industries, such as aerospace and automotive, to evaluate the possibilities of what existed and consider what had not yet been created. Ultimately, we made a decision to replace the hydraulics with an all-electric solution using ball-screw actuation, and that opened up a lot more possibilities for us from a technical standpoint for what we could do.”

Electric motor capabilities on a compact track loader were unknown. There were questions as to whether the electric motors could even turn the tracks, let alone perform any work operations, but, in 2019, to prove its potential, the team took one of its existing models and within six weeks it had developed a prototype.

“We were able to electrify that platform entirely with a battery, electric drives, motors and the electric ball-screw actuation – and the machine worked,” recalls Honeyman. “It was amazing. We showed it to our executive team and they said, ‘keep going’, because it was now a believable concept to them and it just grew from there.”

Powertrain development

Core to the concept and feasibility of the T7X was its adaptation of technology and parts that were already in use and had been proven in other industries. The aim was to take the diesel-fuelled equivalent, the Bobcat T76 compact track loader, and make minimal modifications to the structural design, so much of the work became a parts selection and packaging optimisation exercise.

The first decision to be made was the baseline voltage architecture on which to build. At the time of the machine’s initial development, about five years ago, the 800 V approach, which is now increasingly popular, was in its infancy and the fact that most available parts were based on 400 V architecture pushed the design in that direction.

Pfaff explains: “There are clear advantages in the 800 V systems, two of the main ones being smaller cables that are easier to manage and less copper, which makes it less expensive. But when we started working on this, the 400 V platform that brought EVs to the masses came with validation, testing and availability, so we picked something in between.

“As a result of that, the operating range of the system is between 400 V and 465 V, just above what is used in most of the current automotive vehicles. As we go into the future, we really feel, like everybody else, that it’s going up to the higher voltage system. Our system is capable of that, but right now it is in that middle ground.”

One of the keys to the vehicle’s success was switching the operational functions from hydraulic to electric. To achieve this, the team opted for a motor and ball-screw linear actuator, which converts rotary movement into linear movement, and this was a method they had prior experience with, albeit in a much smaller form.

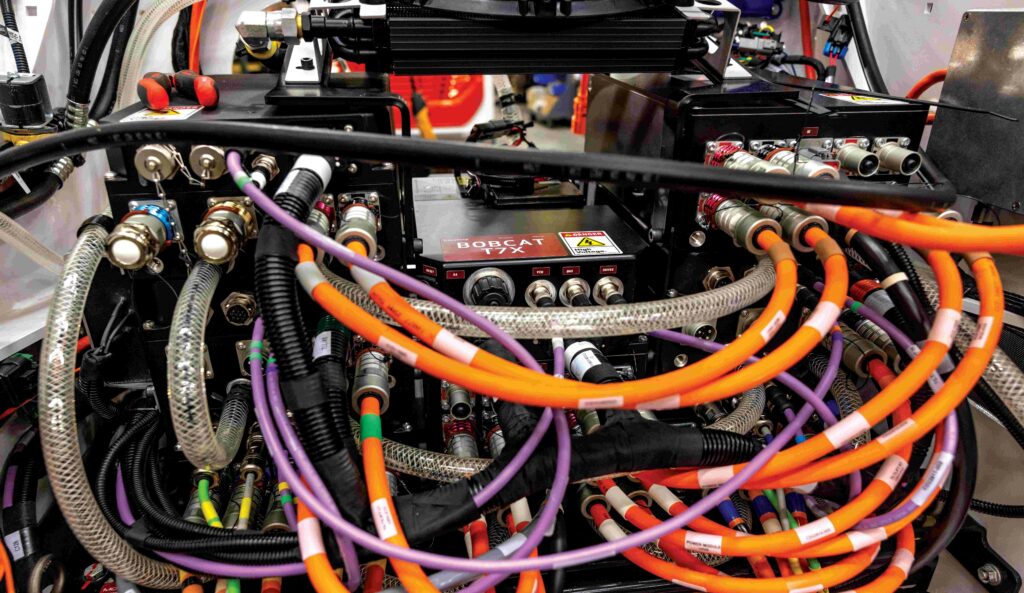

As a result, the vehicle has a total of six motors to power its drive, lift and tilt functions. Two permanent magnet brushless A/C motors are used to drive the tracks in tandem, while the remaining four motors are DC servo devices; two powering the lift arm and two operating the tilt, which then connects to attachments such as a mower, planer, bucket or pallet forks.

Each of the six motors is controlled by its own independent controller, with all six controllers governed by a master computer, which is connected to the joysticks in the machine. The software then tunes the whole system to control those motors, both independently and, most importantly, simultaneously.

“When the operator is controlling the machine, the electronic joysticks are commanding motion to those drive, lift and tilt motors,” says Pfaff.

“The combination of the power going to the motor and the tuning gives the operator the correct application of that power for the work being performed.

“We could have opted for a mixture of hydraulic and electric, but that didn’t make sense. How do we make a hydrostatic motor or a gear pump quieter? How could we minimise leaks? Or how do we make it give feedback to a computer so we know force and position? Some solutions exist in the marketplace, but they’re a compromise in comparison.

“Traction drive systems have been used in construction machinery for years, but the true innovation lies in the application of ball screws, which brings a fresh perspective to the technology. In fact, Bobcat has more than 13 issued patents on the T7X, with several additional patent applications pending.

“The use of the ball screws is really about the forces and application. The challenge with a loader is that you’re using this one piece of equipment for a whole bunch of jobs. It doesn’t just have one application, like a lawnmower. It’s a tool carrier, and the ball screws work beautifully in this application.”

The motors are coupled to a 72.6 kWh lithium-ion battery, chosen with the aim of at least matching the performance of the diesel-powered equivalent. It is sized such that each one of the motors can independently draw its maximum potential, so there is not one motor that would limit the power of another motor based upon its state.

Battery capacity was selected to provide ample working time before requiring a charge. To determine just how much energy was actually needed, the team spent time researching the typical workload of their diesel hydraulic version. This resulted in some interesting findings about how much energy is actually used in everyday operations.

Honeyman explains: “Most construction equipment is only actively used for about three hours per day, and because diesel hydraulic machines need to be on ‘idle’ to build torque capacity, they spend about a third of the day just idling and burning fuel. An electric machine does not need to do that, so that’s a significant reduction in required energy every day.”

The battery contains just over 5,000 cells, which are 18650 nickel manganese cobalt oxide (NMC) in type. When the machine is in normal operation it draws a continuous power of about 40 kW, but this can increase with higher workloads or performance to a peak of around 80 kW, although this will clearly drain the battery more quickly.

Charging is done through an onboard, 6.6 kWh charger, with a full charge taking about 10 hours when plugged into a 220 V outlet, although there are also plans to implement fast charging. The system’s architecture also makes it possible to charge on a remote site without plugged-in electricity using a standard, 220 V, 30 A generator.

Reducing components

The use of electric power for both the drivetrain and work operations has resulted in far fewer component parts, and far less coolant and fluid in use, compared with the diesel hydraulic equivalent. In total, Pfaff says there are now 50% fewer parts and just under one litre of eco-friendly coolant is required, compared with the 216 litres of fluid in the T76.

Pfaff explains: “Most construction equipment requires huge cooling packages for the engine, hydraulics and AC system, and in compact machines that becomes much more noticeable. In this machine the cooler is relatively smaller, and we only need a small amount of fluid running through the traction drives and motor controllers to keep them at temperature.

“In terms of components, every fitting hose, connector, adapter and harness is not just a cost, but also added complexity and risk in terms of runtime. On a diesel hydraulic machine, you have an entire engine, pumps, hoses and multiple individual moving parts, but on the electric loader the componentry is reduced with just a battery, some electric drives and wiring.

“From the outside it is the same machine, but the difference inside is dramatic. It’s far less complex from a piece-part perspective and that should make a lot of people excited, because while our diesel-hydraulic machines are very reliable, each one of those parts represents a possible opportunity to slow down or end your work for the day.”

That component simplification made it far easier for the team to turn that original concept-proving prototype into a machine that has now been sold and sent out to construction sites across North America. Although having to fit in larger system blocks did, ultimately, require changes in some areas of the base machine, its development was still very fluid.

“These machines are compact and everything is very tightly packaged,” says Pfaff. “The electrical components are shaped a little differently to the ones in the T76, so we had to select parts we could package as easily as possible, while the lithium-ion battery we chose was a power-dense solution that allowed us to squeeze more capacity into the machine.

“When we normally design our fuel and hydraulic tanks, our engineers model the voids and crevices, and create a strangely shaped tank. The battery we chose is in a box, different to what you find in automotive, so for this first iteration we kept it simple, kept the box, and worked out what size would fit nicely into the machine in a square package.

“During development we did have to change the lift arm and mainframe. We had to make the cooling area an electronics bay, and we put battery mounts in the area where the engine, hydrostat and hydraulics mounts were. Other than that, the cab is the same, the track carriages are the same and the joysticks are the same.”

Improving performance

Much of the machine has remained the same as the diesel-fuelled alternative – and to an unwitting bystander there is very little to compare between them – but what is not the same is the performance. In the same way that many EVs exceed the acceleration performance of petrol equivalents, that instant torque availability has created superior performance here too.

This performance comes in more ways than one, however, as the machine can not only comfortably power through all types of rough terrain found on building sites, but it also has improved tool actuation, because electrification has enabled it to apply the available torque in different ways to optimise the performance of whatever job it is carrying out.

“In a diesel hydraulic machine, you have to idle up the engine, and to get full torque you have to be at optimal rpm engine speed, so you have a very limited window,” says Honeyman. “On this machine, as soon as you depress the operate button you have full torque, no matter what speed you’re driving or what condition you are in.”

The really clever part, however, is that all this immediately available torque can be directed to where the operator needs it most, and Pfaff explains: “As you drive into a pile and you want to be able to move that bucket up in the air, on a diesel hydraulic machine you’re going to starve the system.

“We have never sized an engine in the past to be able to get all of the hydraulic components to operate at 100% of what they’re capable of, so an experienced operator will know to back off on the joystick for their drive so they get the power they need into their lift and tilt, so they can perform what we call a ‘bobcatting’ function.

“On the electric machine, you have all the power available to both functions simultaneously. We can put full current to the drives, and provide more tractive effort at a time when a customer is trying to move a pile or do other type of work with the attachment, so they can literally drive through a pile. In fact, we had to dial it down to avoid damage.”

The lack of a need for engine idling means the electric machine can stop consuming power as soon as the operator lets off the joysticks. This eliminates the energy inefficiencies experienced in diesel-fuelled versions, which not only need to sit idle while waiting for the next work operation, but are also often left idle when an operator takes a lunch break.

Honeyman accepts that the lack of charging infrastructure needed to support electric machines is viewed by many as one of the biggest trade-offs, but he believes people’s perceptions will change once they understand how efficiently the charge is used and how it is able to deliver such an unexpectedly high usage time.

“Diesel is all over the planet, people can fuel up quickly, they understand it, and there’s a whole infrastructure globally that supports that,” he says. “We don’t have that for electric machines, so there are definite challenges with the perception of the platform beyond the machine itself that are holding some people back.

“But people’s perceptions are based on how their current compact construction machines operate, with one third of the time spent at idle, and we have eliminated that. We have also developed different working modes to optimise battery usage and performance, including an eco-friendly mode, a work mode and a more advanced mode to help conserve energy.”

Those three operational modes provide a similar effect to the ‘turtle and rabbit’ settings found on the diesel machine, but they work in a very different way. Pfaff explains: “In a normal machine, the different modes are based on turning the rpm of the engine up or down, but in the electric machine we are not managing the rpm of an engine.

“Instead, we allow the operator to turn down the maximum level of power, and in some cases that creates a tool for the operator to control the machine in a very different way to how they are used to, meaning that if they are going to do work and don’t need to consume the power, they can turn it down.

“You can either do that with the throttle knob or you can go into the software settings of the machine and turn it down from Mode 3 to Mode 2 to Mode 1, and you’ll only really notice the power decrease in the machine in terms of the velocity of the motors and less in terms of a reduction in power.

“One of the big advantages is that when those motors are operating at higher speeds, they draw more power, so in effect it allows you to decrease the amount of power and increase your run time by either decreasing the mode or just turning down that knob like you would do normally to get less rpm.”

Honeyman adds: “All of this means the machine’s total runtime, depending on application, is between three to five hours, and because of that eliminated idling time, four hours run time is more than enough for a full work day for most customers. In fact, we have found that most people don’t charge every day; they charge every several days, or even every three to four days.

“That brings with it a big financial advantage. Operating this machine is one-tenth of the cost of a diesel hydraulic equivalent machine, so depending on the number of hours, a diesel hydraulic machine may run about £7,500 a year, whereas this is running at less than £1,000 when you consider the cost of electricity and the reduced maintenance.”

Secrets in the software

The secret of this particular EV’s success is the software, which manages the flow between all the different operations. In fact, Pfaff is entirely serious when he says this operates more similarly to a robot than a machine, and during its development the engineers were even able to use the software to unlock features that have previously been extremely challenging to implement.

“Traditionally, development is about structures, powertrain and hydraulics, and you have to go back and forth because of dead band in the system, a lack of understanding of force and position, and power sharing among functions,” says Pfaff.

“Electrification has really turned that development paradigm upside down and this is fundamentally a software machine. Once it’s assembled, we turn to our software engineers to work their magic when it comes to applying this plethora of power in the way the customer expects it to be applied. We discuss how we want the feature to work, the structures and functional safety aspects, and then we can watch this happen through the use of software.

“The machine is tuned so that it has a smooth performance, just like a normal machine, but it is able to give power to all those motors simultaneously, giving you drive, lift and tilt all at the same time. There is no need to compromise any one of those to get the full power you want – and that’s a very different experience than the normal machine.

“We actually have way more power available than we have programmed into the machine, so instead of being challenged with how to maximise the 74 hp in the diesel engine to get it to do what we want it to do, we can use the software to tune the machine and make it adapt instantaneously to get the most amount of performance.”

Applying that power safely requires a delicate balance. But that is far easier in this all-electric machine because, unlike diesel hydraulic versions, the drive functions and lift arm operations are under the control of the same software, enabling programmers to build in functions that let it go beyond standard capabilities without the risk of damage.

Honeyman explains: “The software knows the position of the actuator for the lift arm and tilt at all times, and also what the current load is on the actuator and the electric drives. You don’t know that with hydraulics, and this allows us to do a lot of things with software that we couldn’t do before without the need to use additional sensors.

“As an example, we created a feature we call ‘Beast Mode’, which allows an operator to hit a button on the right joystick, and when the machine is at a certain position and the lift arm is down, the software will provide even more current to help power through something. We only allow that in short bursts though, because we don’t want to damage the machine.

“Equally, we can apply extra lifting power when the lift arm is down, because we know the structures can handle a lot more force. So, in the very first few inches of travel on the lift arm, the software will apply a lot more power, then back off as it raises up in the air, because there are many reasons why you don’t want that much power at that point.

“Another feature we have, which is really interesting to a lot of operators, is automatic bucket shake. This is a manual process on a hydraulic machine, but on this machine the operator can hit another button on the joystick, and it will vigorously shake the bucket to get the material out without them having to put in any physical effort at all.

“We can even use the software to protect the lift arm from being damaged if, as can sometimes happen, a rock gets wedged in a front attachment. On the electric platform, that causes a current spike, which is shown graphically in the control module, so we can back off and protect the machine. We can only do all that by having all this connected information.”

Connected machinery

This software-driven approach also brings other opportunities, including the speed at which the machine can be developed and the ability to make future improvements simply by patching in a software update. It has enabled the team to accelerate production times, send out updates and refine its operation.

“To tune a traditional machine can take an appreciable amount of time,” says Pfaff. “A totally new system can take 12-14 months until we get to the point where we bring customers in. As this machine is a software platform, we can get it tuned up, and get feedback from the customer and make modifications far more quickly.”

The machines are fitted with two-way telematic communication, allowing the team to monitor them in-situ and learn the types of applications for which they are being used. Based on this information, software updates can then be created and sent to the machine remotely, updating the controllers and adding or amending features.

Pfaff continues: “We can look at how the customer is doing their work and then improve the operation purely from a software perspective, instead of having to add another manifold or a pressure sensor that is tied into a controller. That is extremely exciting because it means that what we have right now in production is not the end-all.

“There’s a ton of opportunity now in front of us to keep adding features and capabilities to this platform because it’s smart. There is a whole list of things on our development list that we’ll be talking about more in the future related to force, position and work, and these can get pushed out as soon as we have them.”

Considering the voltages involved and the rugged use of the machine, it is vital that the entire electrical system is robust and has durable connector interfaces. Any faults must be dealt with immediately, so the software has been designed to support an automated system capable of self-detecting any issues during operation.

Pfaff explains: “The cables aren’t like garden hoses feeding water; they’re providing power from the motor controllers to the components and they’re smart. The software is constantly watching all those cables, as well as several very sensitive parts of the system, and making sure they are connected and there are no faults.

“If the connections between the high-voltage battery, the high-voltage controllers and the high-voltage motor are in some way damaged, the machine is smart enough to detect that, understand it and deal with it in an appropriate way long before it ever becomes a problem for an operator or bystander.”

Operational improvements

Electric operation brings with it many operational advantages over the existing diesel hydraulic machines, two of the most significant being the near elimination of noise and vibration. Pfaff has spent a lot of time on the machine himself during testing and he feels this is arguably the most game-changing improvement of all.

“You would never think that the quiet hum of the air-conditioning fan would ever be a bit of an annoyance in a machine like this,” he says, laughing. “We knew it would be quiet, but there’s very minimal sound other than the tracks turning. When you go electric, you minimise sound and vibration, which is really high on our value curve in terms of design features, and it’s just amazing.

“I didn’t think it would be that significant a change, but it really is. People know how sound and vibration can affect them during all types of work, but until you get into the machine and put the hours in, you don’t realise how much it changes how you operate the machine and how you can tolerate the amount of work you do in a day.”

Externally, that lack of sound also makes working in urban environments and close quarters, backyards or even indoors more feasible. The addition of blue flashing lights on the side of the machine – one of the only noticeable external differences between this and the diesel version – are an indication that it is in operation.

The machine weighs around 450 kg more than the diesel version, but this would be a disadvantage in a roadgoing EV. It is actually another benefit here because there is plenty of power to move it along, and when it comes to lifting, the added weight adds a bigger counterbalance to help it lift and manoeuvre even heavier items.

There is a positive effect in cold weather, too, particularly when the mercury drops well below zero. In electric cars, cold temperatures can dramatically diminish range, but in this construction machine the plentiful battery capacity onboard and the way the power is used actually makes it function better in cold weather than its diesel counterpart.

At Bobcat’s North American headquarters in North Dakota, where on the day of this interview temperatures had dipped to -20 C, the effects of cold start on a diesel engine are more apparent than ever. However, with the electric machine, the team has never once had an issue getting it into action.

“There’s a likelihood at really low temperatures that I go out and grab a diesel machine and it may not start,” says Pfaff. “In this, we don’t have to worry about the state of the fuel in the system, the filter, the starter battery – you just get into the machine and it turns on. And because we have a resistive element heater, we have instant heat.

“Some electrics struggle in cold weather, but our machines don’t because of the nature of the way the battery is used. When we’re continually drawing at least 40 kW of power, the battery reaches a temperature that takes a very long time to cool down. Even if it has been really cold for several days, the batteries will tend to stay within their operating temperature.”

Into the future

The T7X is truly pioneering in its industry, and while some smaller manufacturers are known to be working on, or have displayed or produced wheeled designs, the team knows of no other major competitor that has launched an electric track loader like this machine with such innovative use of all-electric drive and actuation.

The company’s website describes the machine as having ‘jaw-dropping’ torque, and Honeyman acknowledges: “Not one customer that has driven this would come back to us due to power or performance and ask for their diesel hydraulic machine back. They want more power, they want to lift more, they want to do it faster, and that’s what this platform enables.

“As well as this, we have developed several models of electric excavators and what comes next will really depend on what our customers value. We’ve been making diesel hydraulic for a long time and we’re going to keep doing it, but customers are asking for this kind of technology, so we’re going to monitor the market and respond appropriately.”

The fact that Bobcat has managed to not only create this machine but also successfully commercialise it demonstrates a new opportunity for the construction industry. It may be just a small loader, but it shows there is the appetite and ability for electrification in an industry that many believed would struggle to expel the use of fossil fuels.

The company has already developed a wheeled, skid-steer loader version, known as the S7X, which contains many similar parts. The differences are the drive system, leveraged from the well-designed existing drivetrain on the diesel-fuelled S76 skid-steer loader, and the replacement of the hydraulic motors with axial-flux motors instead of the ball-screw linear actuator.

Honeyman is confident the lessons learned from the development of the T7X will filter through to some of the company’s other machines, and he explains: “It’s been a pleasure, from a design perspective, to work on an EV platform. A machine like this is based on power, wheels or tracks, motors, cables and software, and we can pivot that very quickly.

“Currently, the electrical components are higher-cost items because they’re produced in lower volumes, so that is one area we need to look to improve on. We will also start to look at the layout, because by taking components from automotive or aerospace, we had to accept compromise on how they are packaged.

“That’s forced us, a little bit, to design the machine around the size of the items currently available. When we get into next generations of this product, we will have designed components that will help optimise that platform. That was probably our biggest trade-off technically: having to accept the components and materials that were available.”

The company has now electrified two loaders – the T7X and S7X – and has developed multiple electric excavators, as well as an electric zero-turn mower. They are now looking to optimise the existing platforms using what they currently have, but also working on new components and lowering costs to enable greater volume production.

Electrification is certainly showing its potential for this industry, but this is not yet the end of the road for diesel-powered machines in construction.

In fact, Honeyman believes the new directions that have been pioneered on the T7X (and other electric machines) could also lead to improvements in existing diesel ranges.

“We’re working with multiple battery and component manufacturers to optimise these electric platforms, but it will also travel the other way,” he concludes. “We’ve learned a lot, and we’ve seen some opportunities to potentially take some of the electrified components and use them on diesel hydraulic machines in some areas.

“Electric actuation is a great example. We could apply that approach to different parts of our line-up and still be diesel hydraulic primarily. I think you’re going to start seeing that as well. We’re going to monitor what we have developed, continue to look at ways to implement new innovations, and ultimately use it to create many new improved models.”

Specifications

T7X Compact Track Loader

Rolling chassis:

Length without attachment: 117.6 in

Width: 78 in

Height: 81.5 in

Operating weight: 12,590 lb

Motor: permanent magnet (brushless)

Power: 100 bhp

Battery: 72.6 kWh lithium-ion battery

Charging: 12-hour charge time with

240 V, 40 A outlet Suspension: Solid-mounted undercarriage

ONLINE PARTNERS