Battery leak testing

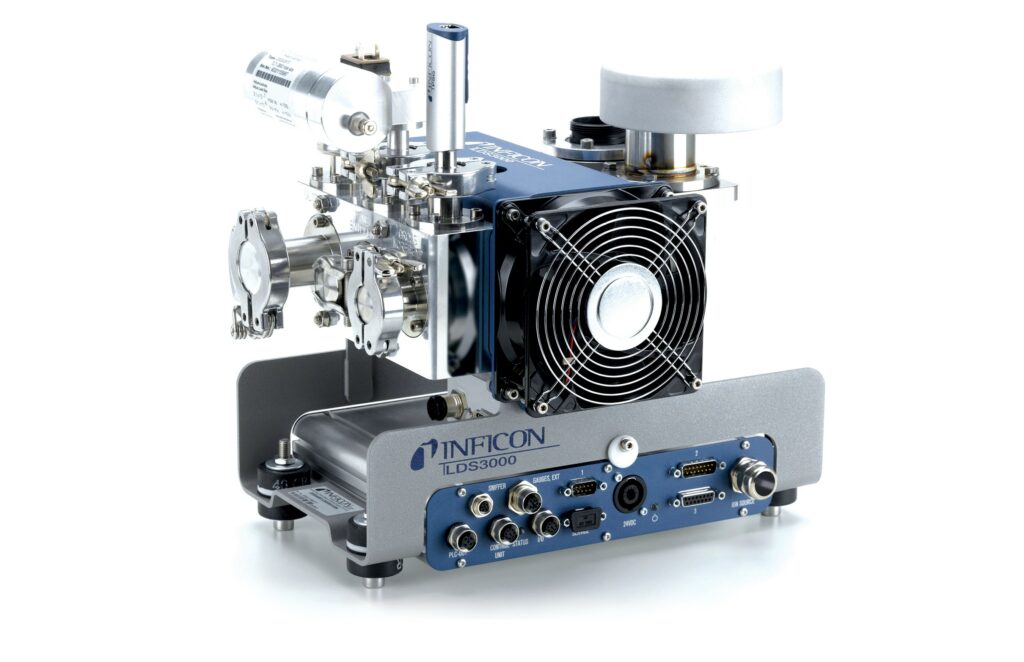

(Image courtesy of INFICON)

Accurate and reliable testing

Peter Donaldson delves into the world of battery leak testing

With the exception of old, British motorbike engines – it was said that if they’re not leaking, there’s no oil in them – leaks from anything are usually a sign of a problem.

The escape of liquids such as coolant and electrolyte are undesirable, and the emission of gases can be the first warning sign of a thermal runaway.

Also, intrusion of water or road debris from the vehicle’s exterior into the battery enclosure can cause corrosion, shortening battery life, generating heat and even potentially triggering a thermal runaway.

Therefore, reliable and accurate leak detection is essential at every stage of an EV battery’s lifecycle.

During manufacture, testing is focused on quality control. It is vital that customers define the specific failure they aim to prevent (such as electrolyte leakage rather than water ingress), as this dictates the required leak rate sensitivity, which can differ by a factor of 100 between application specifications. Automated able to handle, say, 200 parts per minute, with reliable repeatability and data tracking is critical in high-throughput production.

At the dealer or vehicle repair level, in-service leak detection is possible. These systems prioritise simplicity and lower cost than those used in manufacturing due to infrequent use, which might be as little as once a month. A vehicle manufacturer is likely to have orders of magnitude fewer production lines to equip (perhaps as few as 50). At this level, slower testing is acceptable, while durability is less critical.

Leak detection systems that may be built into battery packs differ from those used in production and during servicing. Sensors monitor concentrations of target substances rather than flow rates, and the distinction between them is important. Systems also have to be much cheaper, with sensors costing just a few dollars each. Relatively slow response of 30 seconds or so is acceptable, but performance must remain stable over many years.

At first, battery manufacturers often focus on detection methods sensitive enough to find the smallest leaks, but matching the leak rate to the failure being prevented avoids unnecessary expense, as does matching the required testing speed to the application. Also, application context is crucial, with, for example, cell-level electrolyte testing, pack-level water ingress detection, and cooling circuit checks all needing tailored solutions.

Several testing methods are employed in manufacture, including tracer gas (helium and hydrogen), pressure decay, mass spectrometry and ultrasonic crack detection.

With tracer gas testing, parts are filled with He or H2 and placed in a sealed chamber, and gas detectors show any leakage. Broadly, there are two approaches: the vacuum method and the sniffing method. In the first, the battery case is placed inside a vacuum chamber and pressurised with helium. A mass spectrometer-based leak detector inside the chamber but outside the battery case detects escaped helium. In the sniffing method, the battery case is filled with helium again, but this time a sniffer probe is moved along potential leakage points such as seams, welds and connectors to detect and locate leaks.

The main advantage of tracer gas testing is its sensitivity, being able to detect leaks as small as 10⁻⁹ atm cc/s (0.000000001 cc of the gas escaping per second under a pressure of one atmosphere). Also, it does not damage the battery and it is highly reliable. The principal drawbacks are the expense of the required vacuum chambers and mass spectrometers, the complexity arising from the need for well-sealed environments to avoid false positives, and the handling risks, cost and scarcity of helium.

In pressure decay testing, gas is injected into the coolant circuit and, separately, the battery casing, and the pressure monitored. After a set dwell time, the pressure is measured again, and if the pressure drops below a threshold a leak is confirmed.

Increasingly seen as best practice in volume production, advanced pressure decay testing takes seconds or minutes, minimising effects of temperature variation. However, it is less sensitive than helium/mass spectrometry testing, only detecting leak rates down to 10⁻³ atm-cc/s, and temperature variations can cause significant errors in some systems.

In ultrasonic testing, microphones listen for sound waves at frequencies higher than 20 kHz that indicate escaping gas. Non-invasive and quick, it is typically used to identify structural defects in cells and modules. It can be used in combination with compressed air that forces leaks, or passively to listen for unforced leaks.

Ultrasonic testing does not require a vacuum chamber or tracer gases and identifies leaks in real time. However, it has similar sensitivity limitations to pressure decay testing, it can be susceptible to false positives from background noise, and the interpretation of signals requires expertise, as ultrasonic leak detectors do not read a quantitative leak rate.

In storage, batteries are monitored for electrolyte leakage or gas emissions. One of the technologies used is gas detection using sensors that react to gases such as hydrogen, carbon dioxide, or volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted by leaking electrolyte or during thermal runaway. Although cost-effective, these systems are not selective, responding to all hydrocarbons and solvents.

Another is thermal imaging using infrared cameras, which reveal the heat signatures of leaks and short circuits. Thirdly, optical emission spectroscopy analyses the light signatures of gases and is highly sensitive to those of interest, enabling early warning.

In operation, gas detectors can be used inside battery cases, complementing the indirect detection capabilities of the battery management system (BMS) and isolation monitoring circuitry.

Continuous processing of voltage, current and temperature measurements by the BMS in real time can indicate leakage or internal battery faults. Also, acoustic emissions-monitoring systems can be used to listen for sounds generated by stress or cracking within the battery pack, providing an early warning of structural failures in predictive maintenance applications.

As battery designs continue to diversify, leak testing systems have to keep up while offering greater precision and reliability.

(Image courtesy of ATEQ)

Under pressure

Advanced air-pressure differential decay testers can measure larger ranges of volume and pressure, and cancel out the noise of factory environments to improve the accuracy and reliability of in-line testing. One of the latest systems features a differential sensor with a range of 20 pascals (Pa) and sufficient sensitivity to detect pressure variations as small as 0.001 Pa.

Using a controlled air-injection process, this system pressurises the battery and a reference element. Once the target pressure is reached, the pressurisation stops, allowing the system to analyse pressure variations and accurately determine the leakage rate in millilitres per minute. The system’s software enables users to monitor the entire pressurisation cycle, continuously track leakage rate during the test, and optimise testing parameters.

Testing battery components quickly is critical in production, and one innovation in this area is the measurement of discharge current to detect small holes in plastic parts, such as pouch cells. The method works by applying a high voltage to a sharp probe that is brought close to an earth-connected base supporting the cell under test.

If there is a hole in the cell, ions will start moving from the earth to the sharp end of the probe, resulting in loss of power, and this will be interpreted as a leak. The pass/fail decision is based on the measured percentage of the cell’s nominal voltage, which reflects the discharge current. While this does not quantify the leak rate, the developer claims it is the fastest ever device to detect a leak in a go/no-go process, achieving cycle times of under 0.7 s.

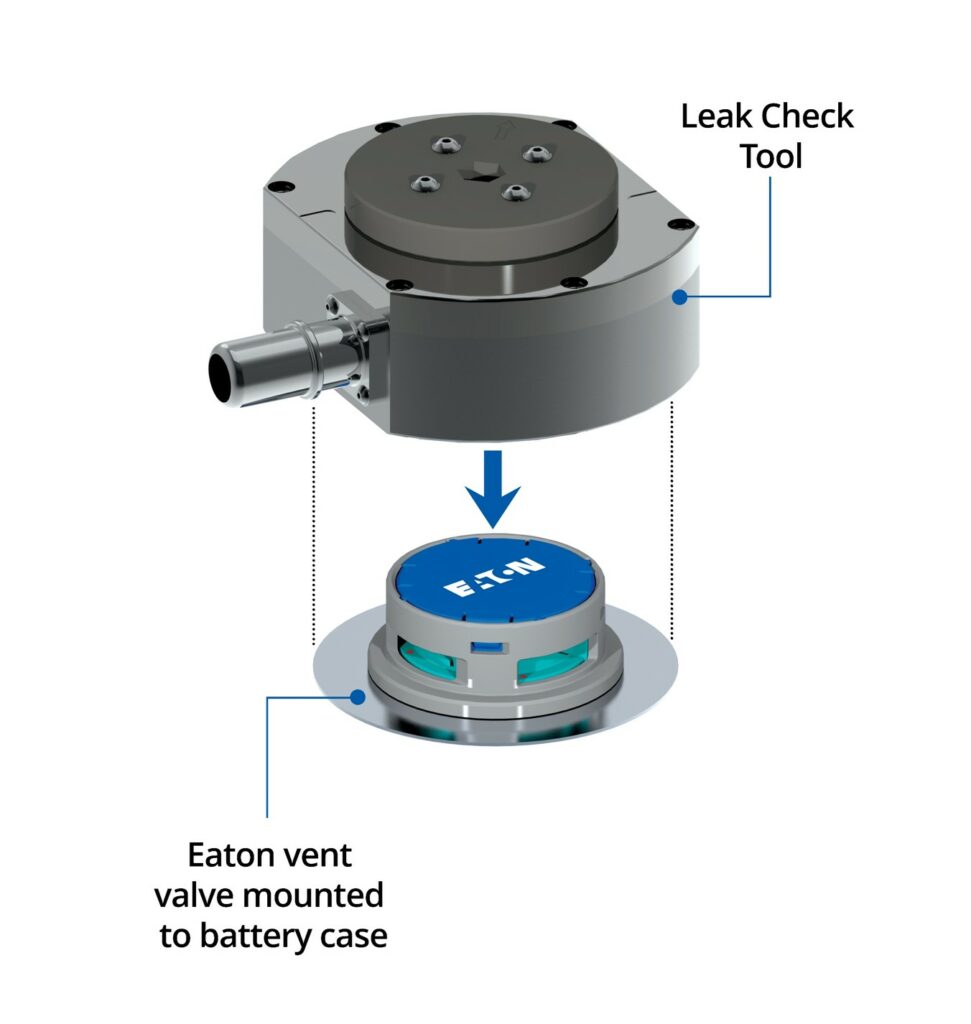

Most battery packs feature vent valves with permeable membranes that allow gas and vapours to pass through while sealing the pack against water ingress. This can make it difficult to test the seal between the pack housing and the vent valve, but in one recent innovation a feature that enables leak checks is integrated into the valve to allow sealing to be tested after the valve is installed. This supports testing during manufacture, as well as in maintenance and repair. In the company’s own tests, it says, the filling of a battery pack with 120 litres of free air volume has been achieved in less than 5 s.

(Image courtesy of ATEQ)

Getting specific

Detection and identification of specific gases is improving with the application of techniques such as colour-changing chemical reagents and a reactive gas, and refinements to instruments based on mass spectrometry.

The colorimetric chemical technique is a recent innovation, taking advantage of the fact that, like all chemicals, new compounds that form when two or more molecules meet have unique molecular structures that absorb light differently, giving them specific colours. Creating a leak detection system depended on selecting a safe combination of reactive ‘challenge’ gas and colour-changing chemical reagents.

The technique works by first placing the colour-change reagent over the welded or sealed areas on the outside of the battery enclosure and then pumping the challenge gas into the enclosure at low pressure. As the gas diffuses thorough the case, it reveals and permanently marks any leak points.

The most critical task in developing the system was finding the right combination of challenge gas and colour-change reagent, both of which had to be low in toxicity at the concentrations used, non-flammable, harmless to all the materials in the battery, inexpensive and plentiful. The gas had to be effectively absent from the air, while the colour-change reagent had to respond to the gas but not to the air.

The gas chosen was ozone (O3), while the developer formulated its own colorimetric reagent. The one they came up with can be applied to a tape, and it changes from clear to purple permanently within seconds of exposure to low concentrations of ozone.

The sensitivity of this technology depends on factors such as the volume of the system, the pressure of the challenge gas and the size of the hole through which it is leaking. The gas changes the colour of the reagent media at concentrations below the limit set by the US Occupational, Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the manufacturer says.

In tests, the time taken for the reagent to change colour varied with hole diameter – the larger the hole, the faster the colour change – but it was not influenced significantly by a small change in gas pressure.

While the technology has been created to detect gas leaks, the developer notes that it is possible to formulate another colour-change reagent to interact with liquids or electrolytes, depending on their underlying chemistry. Further, the challenge gas could be added to the battery and used for continuous monitoring.

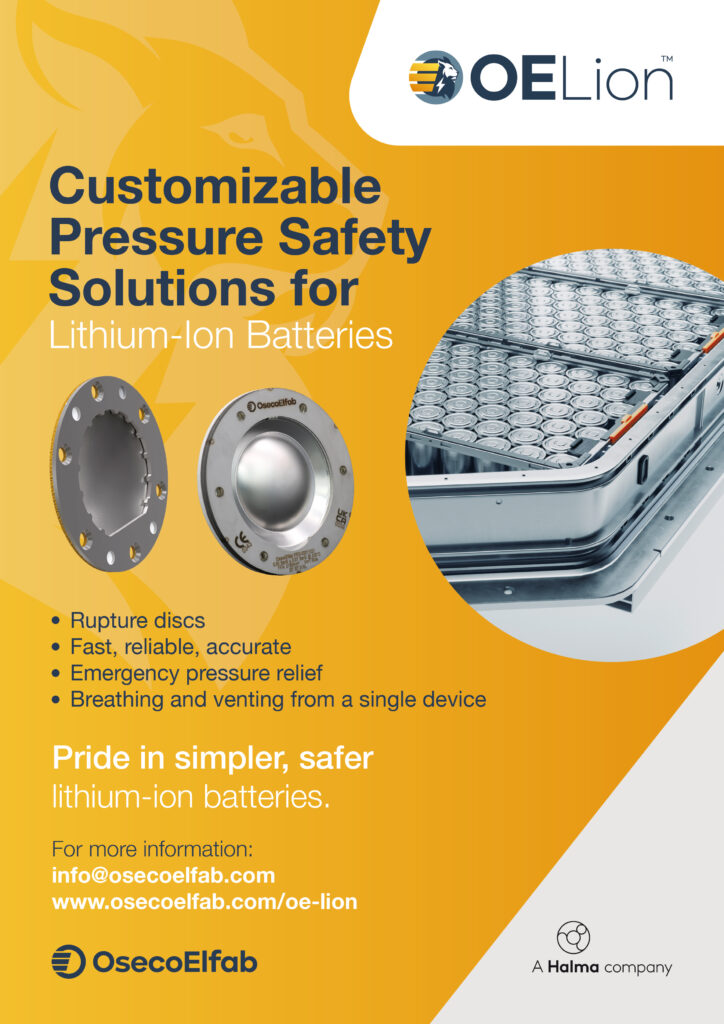

Systems based on mass spectrometry can detect leaks of all gases and liquids, including electrolytes through the use of tracer gases or the final medium. The required sensitivity depends on the application, and different detectors have different sensitivities, with some capable of detecting leak rates as low as the standardised limit of 10⁻¹² atm cc/s. This means that under a pressure difference of 1 atmosphere, only one-trillionth (10⁻¹²) of a cubic centimetre of gas escapes through the leak every second.

That’s a tiny leak and such sensitivity is not required in the battery industry, but it illustrates the capability of the technology. As a rule of thumb, real requirements range from a few milligrammes per year up to kilogrammes per year.

(Image courtesy of Eaton)

Systemic needs

Detection capability alone is an insufficient metric, one equipment manufacturer cautions, adding that most customers need assistance in developing a complete testing process. For example, consultations explain how to fill the test article with tracer gas, take the gas out of the part, reclaim and reuse expensive gases, and how to establish proper leak rates for their scenario. All the detectors feature digital or analogue interfaces that allow operators to track real-time data for immediate detection and later statistical analysis.

As an alternative to tracer gases, such as helium and hydrogen, some systems use a signature air, which is typically a proprietary mixture that creates a vapour designed to be detected by the manufacturer’s own equipment, such as handheld sniffer devices.

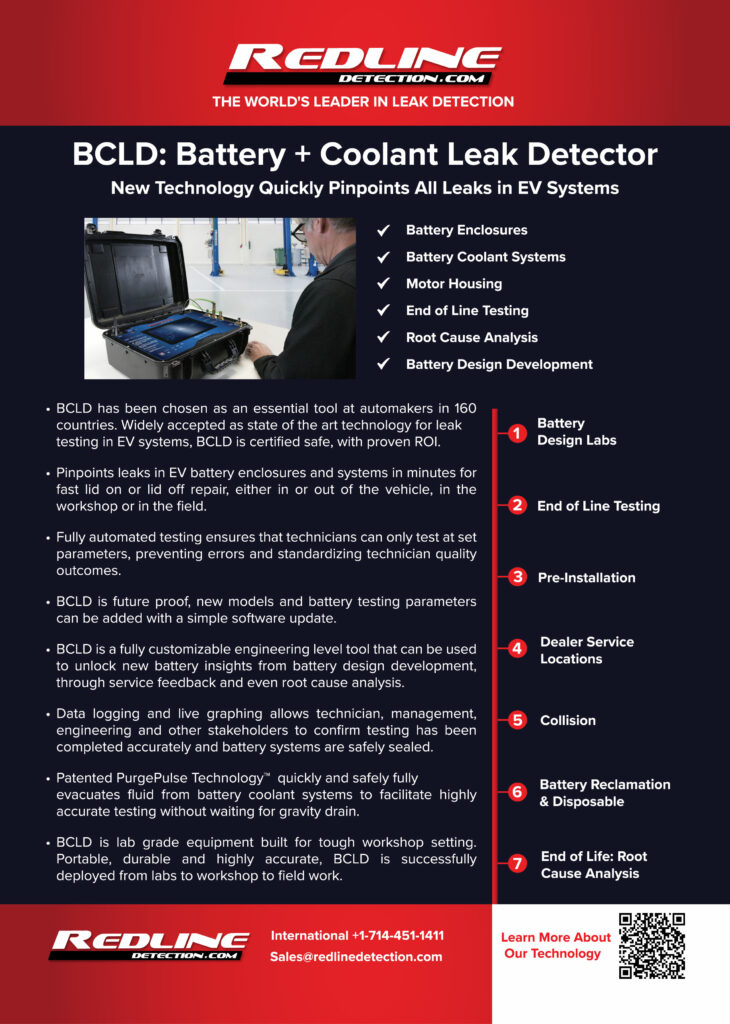

This technology is designed to find gas and coolant leaks in batteries, and it can be tailored to the OEM’s needs in terms of parameters such as sensitivity, and it can be updated to handle new vehicle models and battery configurations with a software update. It can also be customised to solve particular issues.

For platform standard scenarios, one equipment developer resolves to five decimal places when measuring in PSI, enabling a significant reduction in testing time while maintaining accuracy and repeatability. It emphasises that the equipment can find very small leaks that are undetectable using outdated methods such as soapy water.

In many applications, it is important to provide live graphing and reporting at every diagnostic stage, and the battery and coolant leak detector does that, capturing data continuously, followed by extensive reports that can be saved and sent to stakeholders.

Leak detectors used during manufacture are typically designed to find just one type of gas: the tracer gas or signature vapour they are expecting. Dual gas detectors that target helium and hydrogen are available, and they are tuned to detect one type of gas at a time. Those based on industrial-grade mass spectrometers offer high sensitivity, fast response and a compact footprint.

Such selectivity is very important to avoid false alarms. Unfortunately, all gas sensors have issues with reactivity to a variety of chemicals, so systems have to be engineered and operated to minimise the risk of confusion.

(Image courtesy of EWI)

Clearing the background

For example, EV thermal-management systems increasingly include refrigerant circuits, and if there is a nearby refrigerant filling station it may emit that gas through connectors and create a background of that gas, making detection more difficult. Therefore, advanced leak detectors incorporate intelligent signal algorithms developed to differentiate between emissions due to leakage and background gas emissions.

In general, leak testing systems can cope very well with the range of sizes and pressures they are likely to encounter in batteries, from small components to large, complete packs. Precision pressure-based testers can cover ranges from full vacuum up to 20 bar, and volumes from 0.1 cm³ to 1 m³. One supplier emphasises its ability to test everything from a tiny cooling plate for a car to a “massive” bus battery enclosure within a single platform.

With vent valves incorporating pass-through leak check devices, the limitations are set by the robustness of the battery case and other components.

While colorimetric leak detectors are not limited in the size of the parts on which they can be used, as parts get bigger, the system will need a larger gas generator and/or higher pressure to cause the colour change within a specified time.

(Image courtesy of INFICON)

Integration issues

Integrating leak detection into battery manufacturing processes is essential for quality control as production rates and volumes increase, and such integration can become complex. Sniffer leak detectors can be used as stand-alone devices, and it is possible to build a system that integrates a vacuum leak detector only, but to create a system optimised for speed, throughput and repeatability takes more complex technology, typically provided by system integrators. In support of this, leak detection suppliers build a variety of digital fieldbus interfaces into their products, including Ethernet, PROFIBUS, as well as analogue interfaces.

One supplier says its metal-ion battery leak-test capability is now in its third generation and has developed rapidly, along with the industry. Battery leak testing was first required by r&d departments that wanted to test about 20 parts a day; they now offer detectors that can easily test 200 cells per minute.

Calorimetric testing measures the heat released from a substance, which can be used to detect leaks. It can be integrated into existing production lines or quality control labs, so long as there is space and power for the challenge gas generator, booster pump and colour-change media, which can be taped, brushed or sprayed onto the part under test.

Battery leak and coolant detection is being integrated into production lines for end-of-line testing, and at quality checkpoints throughout the life of the vehicle for preventive maintenance and repair. At one vehicle OEM, if an EV fails coolant filling on the production line, it goes to the service area for testing to pinpoint the leak, so technicians can make a repair, perform a verification test and release the vehicle back onto the line.

The developer eases integration by offering a version with an embedded screen and one with an interface that runs on a PC, and it uses industry standards to guide the application programming interface (API), simplifying communications between the software and hardware components of the detector and the host system.

While most leak testers are agnostic to battery chemistry, they tend to be designed for use with liquid electrolyte batteries, although one supplier we asked is developing the capability to test solid-state batteries. Another notes that temperature is important, recommending that testing is carried out in steady state environments where all components are in thermal equilibrium.

In operation, batteries in e-mobility applications rely more on the BMS to detect problems that could cause or be caused by leaks, although a growing variety of aftermarket leak testers are available to authorised repairers. These systems don’t have to produce results as quickly as those used in high-volume production and a response time of several seconds is generally acceptable, so the sensors can be simpler and less expensive, making building in dedicated leak sensors more attractive, particularly if they include wireless communications to support remote data collection.

Also, leak-check vent valves can support portable pressure testers so long as they are accessible, preferably without having to remove the battery.

(Image courtesy of ATEQ)

False positives/negatives

Consistently reliable results are essential to all testing systems, and the rate of false positives and false negatives is a crucial measure of that reliability.

One innovative way of minimising error in differential pressure decay testing involves cancelling out any background noise that can affect the measurements. Sources of disturbance in factories can include temperature variations caused by opening doors or windows, and the operation of fans, heating, ventilation and air-conditioning systems, while the time of day, sound levels and weather conditions can cause pressure variations, and machine movement, wind, forklifts and even music can cause vibration.

A leading supplier of differential pressure decay testers has developed an automated learning process that measures such sources of noise and compensates for them.

Even with leak detection systems that have inherently low rates of false positives/negatives, such as mass spectrometry, achieving this requires careful handling of the test gas to minimise the concentrations in the environment around the tester, as well as proper use of the equipment. To achieve this, a leading supplier offers intensive consulting services on how to design the leak testing procedure.

With colorimetric testing, a false positive is highly unlikely because of the chemistry of the colour-change media. A false negative can be avoided by carrying out sufficient tests on leak holes with diameters of interest. This would include varying the challenge gas pressure and noting the time to colour change. Smaller holes will take longer to detect, so a minimum hole size and maximum time to colour change must be established before implementing the system on the manufacturing line.

While test labs have tightly controlled conditions, and modern production lines tend to be very clean and tidy, testing systems may have to cope with less than ideal environments, perhaps with high temperatures or vibration, and some technologies are more sensitive than others. Advanced air-pressure differential decay testers that can resolve pressure differences as small as 0.001 Pa, for example, need a very stable environment.

In contrast, colorimetric systems are practically unaffected by vibration, and although the chemistry has not been tested at high temperatures, operation at up to 100 C could be possible, a manufacturer notes. All leak detectors face limits to the temperatures in which they can operate properly, and ranges can extend from 10 C to at least 30 C and sometimes 35 C.

Dry rooms also present challenges to some types of leak detectors, as anything that can introduce moisture must be avoided. This precludes older methods that use fluids such as soapy water, liquid-based fluorescent dyes and any medium that has to be sprayed. Mass air flow or pressure decay testing that uses humidified air are also unsuitable (systems using dry air are available), as are methods of hydrogen tracer-gas detection that use moisture-based sensors. Preferred alternatives for dry rooms include helium mass spectrometry, ultrasonic leak detection and vacuum decay testing.

As with pretty much all industrial equipment, leak detection systems inspire more confidence if they comply with widely recognised quality standards from bodies such as the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO), the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) and safety certification company Underwriters Laboratories (UL). European Economic Area CE compliance is also important.

One supplier we consulted emphasises that its air-based and discharge current-based technologies are developed under an ISO 9001-certified quality management system that ensures compliance with automotive and industrial regulations, while also aligning with industry-specific requirements.

The standard relevant to leak testing-compatible battery vent valves is SAE J3277-1 JAN 2025, stating that the first priority is leak testing the sealing surface between the battery-pack housing and the assembled components. Many more regulations are for leak test equipment, including the European Commission’s Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS3), compliance with US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) rules, UK Conformity Assessment (UKCA), Eurasian Conformity (EAC), Korea Certification (KC) and Japan’s Product Safety Electrical Appliance & Material (PSE) certification.

Most suppliers find they must comply with several sets of standards across different markets and for various types of equipment. One manufacturer notes that all its detectors fulfil CE standards and most are UL-certified, while its handheld devices are all SAE-certified. Leak detection standards are still evolving and the company serves on SAE committees to help develop them.

Care and feeding

Maintenance requirements vary according to the leak detector maker and system type. Many manufacturers recommend annual maintenance and calibration to ensure accuracy and reliability. Some companies offer ISO 17025-accredited services for certified calibration and support. Some systems include seals or fixtures that can be serviced as part of routine preventative maintenance schedules, reducing unexpected downtime.

Maintenance needs differ, based on the type of data required. Systems providing qualitative leak detection typically need regular servicing of electromechanical components, such as pumps and gas generators, but they do not require calibration. Quantitative systems, however, require calibration of parts such as mass flow sensors to maintain measurement precision.

Some advanced leak detectors feature extended maintenance intervals, with sensors warrantied for several years. Maintenance is often limited to replacing dust filters, small mechanical parts or oil reservoirs in vacuum pumps. Many detectors remain in operation for decades, with upgrades driven more by technological advancements than equipment failure.

Certain manufacturers integrate self-calibration or optimised components to minimise maintenance needs. Some systems automatically calibrate to the testing environment before each use, reducing the burden on operators. Factory calibrations are verified as per OEM specifications, eliminating frequent adjustments.

Overall, maintenance requirements depend on the specific detection technology, system design and intended application, with some units requiring minimal servicing beyond basic component replacement.

Lifespan varies by design and maintenance requirements, but many leak detection systems are engineered for long-term durability with minimal upkeep, making them a long-term investment. Some equipment is built to last over 20 years, requiring only minor component replacements, such as valve seals and filters. Other systems are designed for at least 10 years with proper maintenance.

Systems using colour-change detection media or challenge gases need these materials replenished regularly, but that does not affect the system’s overall lifespan. Some advanced systems incorporate zero-maintenance components, reducing the need for servicing.

Modular or software-updatable architectures increasingly feature, allowing systems to adapt to new vehicle models, battery configurations or testing standards without requiring hardware replacements.

Costs and scalability vary, depending on the system design, specific product features and scale of manufacturing. Some simpler leak detection systems, typically for production testing, range from $10,000 to $35,000, with some models reaching up to $50,000, although these prices cover the detection technology only, not complete systems, according to a leading supplier of mass spectrometry and vacuum decay equipment.

More complex setups, such as those integrated into production lines, can cost $100,000 to $200,000, depending on the level of automation, the number of test chambers and throughput capacity. However, additional features such as multi-chamber systems and high-speed pumps can scale the cost, based on performance needs.

Many leak detectors are modular, allowing for easy adaptation as production requirements grow. For instance, detectors with a single test chamber can be scaled up by adding more chambers or larger pumps to meet the demands of high-volume production lines.

Systems can also be customised for specific sensitivities, meaning users can choose a detector with just enough sensitivity for their needs. This allows for faster test speeds while avoiding overpaying for excessive sensitivity.

Future directions

As leak detection requirements and technologies evolve, a number of trends are observable. One is a focus on smaller leaks and more sensitive, automated testing. Another is increased use on production lines of 100% rather than sample testing, along with data-driven early warnings to spot production issues before failure thresholds are crossed. Also, there is potential benefit in exploration of visual technologies from cameras to X-rays in the longer term, although resolution and AI interpretation need to improve before they are viable for the detection of the smallest leaks. For the moment, traditional methods proving substance escape remain most reliable.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the following for their help with this article: Jean Luc Regef, CEO, and Jeremie Hernandez, Technical Training Manager of ATEQ Group; Jens Buhlinger, Battery Technology Development, Eaton Mobility Group; Jeff Ellis, senior technology leader at EWI; Sandra Seitz, automotive market manager, leak detection, at INFICON, and Alex Parker, president of Redline Detection.

Click here to read the latest issue of E-Mobility Engineering.

Some suppliers of battery leak detection solutions

Agilent

ATEQ

Cincinnati Test Systems

Eaton

EWI

E-XTEQ

Fives Group

Fortest

INFICON

JR Automation

JW Froelich

Marposs

Poppe + Potthoff Maschinenbau GmbH

Redline Detection

Vacuum Instruments Corporation

Zeltwanger

ONLINE PARTNERS