Clipper Automotive Clipper Cab

(Images courtesy of Clipper Automotive unless state otherwise)

Hire ambition

This e-taxi, converted from the iconic London black cab, is set for real-world trials. Peter Donaldson explains how it’s being developed

The urban jungle is a natural environment for battery EVs, as they can take advantage of its stop-start traffic to recover energy through regenerative braking. The iconic black cab, therefore, is a natural target for conversion to a BEV, particularly as there are large fleets of these long-lived vehicles with diesel engines facing non-compliance with tightening emissions regulations.

Furthermore, financial incentives are available from national and local governments keen to show their green credentials by supporting public transport options with no tailpipe emissions. Clipper Automotive intends to capture a substantial proportion of that market with its Clipper Cab, a conversion of the TX4 built by the London Taxi Company (now known as the Asia Cab Company).

The prototypes use powertrain components from Nissan Leaf BEVs or E-NV vans, chosen for their technical maturity, proven longevity and availability at relatively low cost, explains Clipper Automotive EV engineer Harris Medwell. Early production examples will also retain those Nissan components, which include the battery modules, BMS, DC-DC converter, inverter and motor, along with a Tesla onboard charger and Clipper’s own ECU.

Leaf recycling

Most of the componentry is recovered from written-off vehicles. “There is arguably some risk in that with some of the components, but with batteries you can test the state of health, so unless the pack has been impacted – which you can tell for yourself – the risk is easily mitigated,” Medwell says.

“If it were a 100,000-mile car with a battery state of health at 70% we wouldn’t touch it, but with most newer Leafs, especially those with 40 kWh packs built from 2018 onwards, the mileages are relatively low and the state of health percentages are in the high 90s.

“When it comes to other components, Nissan has used exactly the same motor, for example, from the first-generation Leaf to the ones they build now. The motor is ‘bomb proof’ and would be the last thing to go wrong on a Leaf, so we are very confident when taking a motor out that it will run absolutely fine, and you can get them stripped and refurbished anyway.”

Clipper tests each second-hand motor, inverter and so on using a rig that includes a ‘dummy’ battery (a 24 kWh pack the company assembled for the purpose) and the ECU it has developed for the cab, although that takes place after purchase from the breaker, from whom there may not be much comeback. The financial risk, however, is small because a good used Leaf motor can be obtained for under £1000 and an inverter for around £200 – a small proportion of the £8000-9000 cost of a written-off Leaf, the bulk of its value being in the battery.

While the second-hand ethos is quite eco-friendly, it is as much about developing the proof-of-concept vehicle, early prototypes and small-scale production, although the policy is likely to change to cope with larger production quantities, Medwell says.

“We will definitely keep to it though for the first 13 months, and the first 10-20 cabs. When we are looking at hundreds of cabs, that is when we will start to go elsewhere.”

Proof of concept

At the moment there are three Clipper Cabs in existence. The first is based on an older TX2 with the diesel powertrain removed and the chassis fitted with components stripped out of an E-NV van. It uses everything from the battery, ECU, inverter and motor to the throttle pedal, steering column and windscreen wiper motors. The result is a proof-of-concept vehicle that moved under its own power well enough to obtain funding from the UK government’s Niche Vehicle Manufacture scheme.

“Once we had proved we can do it, we changed tack a little,” Medwell says. “We went down the open inverter route, which allowed us to modify the Nissan motors and develop our own ECU.”

The open inverter concept began as a project focused on a scratch-built inverter and ECU hardware using open standards, but has since shifted to using open ECUs to control OEM inverters, including over a CAN bus system.

The company then built two more vehicles to the revised specification, which Medwell describes as production-ready prototypes, based on the TX4. Over the past seven months, they have been driven the length of the UK by Clipper staff, who used the opportunity to canvass local authorities to find out what the company needs to be able to license the vehicles as taxis in their jurisdictions.

“Usually it’s things like age limits, so we are trying to convince them that, as this is a zero-emissions vehicle, age limit might not apply,” Medwell says.

Taxi cabs as well as private hire vehicles are subject to a 12-year age limit, after which they need to be replaced with cleaner vehicles. The rule prevents drivers from buying second-hand EVs, although they can still buy new diesels. Some local authorities are dropping the age limits and switching to emissions limits for diesels and/or annual or six-monthly condition inspections.

Type approval and IVA

As the Clipper Cab is a conversion of an existing type-approved vehicle, there are limits to the modifications that can be made without voiding the approval, with critical components and systems including the chassis, brakes and steering in particular being tightly controlled. The regulations set out a points system to rate modifications, and a score of more than eight voids the type approval, Medwell says.

“We therefore make sure we don’t drill any holes in the chassis, we don’t touch the braking system or the steering system, and we attach new components to existing mounting points,” he says. “Obviously the brakes and steering are now electrically powered, but the system is still the same and we don’t go over design loads. We are only 70-100 kg heavier than the original TX4, which is well within the design load, so the suspension and drum brakes are fine, but we have regenerative braking as well.”

The TX4’s standard hydraulic steering system is retained, for example, but it now has an electric pump driven by a Vauxhall Astra steering motor.

Although Clipper Automotive’s modifications comply with the existing type approval, the company also puts each electrified cab though the Individual Vehicle Approval (IVA) process, which involves an inspection by the UK’s Driver and Vehicle Standards Agency (DVSA). Many local authorities require either type approval compliance or an IVA, but Clipper has chosen to go down both routes for extra assurance.

“We have made a point of painting everything we have added in quite bright colours so that when you look at it, especially when somebody inspects it, they can see exactly what we have put in,” Medwell says.

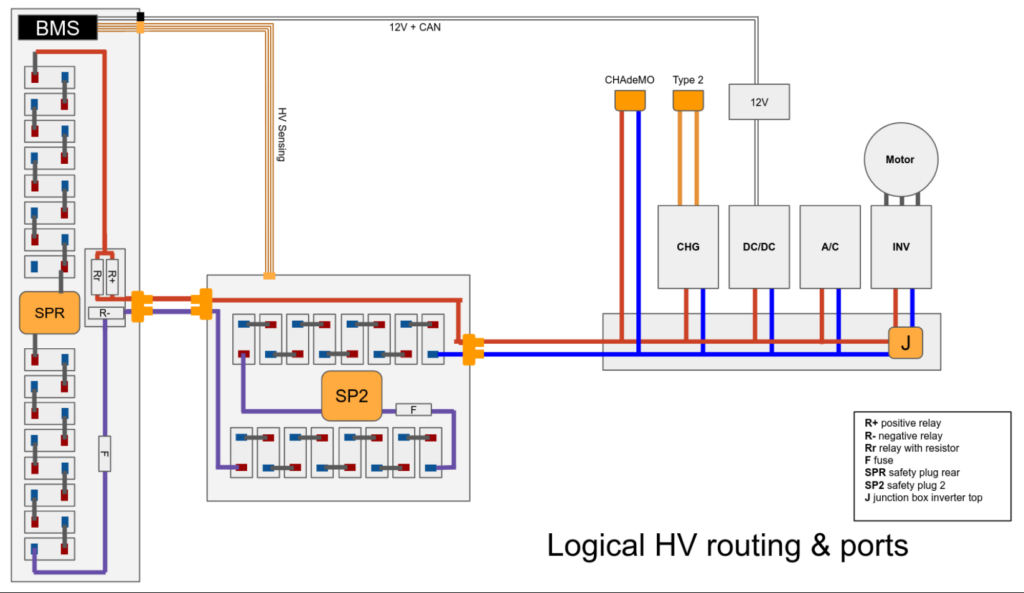

Also, the cab has to have a high-voltage ticket from the UK Vehicle Certification Agency (VCA), which involves testing to make sure there is no danger to anyone inside or outside the vehicle. While most of the electric powertrain is unmodified with respect to the Leaf or E-NV van from which it came, Clipper makes its own front and rear battery boxes to contain the original cells from the Nissan pack because of the limitations presented by the TX4’s structural architecture.

That means all the connections between the cells inside the boxes, the HV and BMS connections between the boxes and from the battery to the inverter have been engineered by Clipper. The original Nissan 3 kW onboard charger has been replaced by a 7 kW Tesla unit.

Although Clipper repackages the original cells into two boxes, it follows the Nissan connection scheme between cells in the modules, and between modules in the pack. That’s done to preserve the capacity and voltage, and to ensure it performs as designed, particularly when controlled through the Leaf’s BMS.

New BMS wanted

A new BMS might be on the cards for later production vehicles, however, in order to simplify the battery pack wiring and to gain extra efficiency, Medwell says, as the split pack makes the BMS wiring more complicated. There are effectively two battery packs, so either the sensing cables have to run between them or there must be two BMSs in a primary-secondary configuration, he explains.

The present set-up runs the BMS cabling and HV power cabling in extended looms between the front and rear battery boxes. The extra lengths of cable do cause a very small voltage drop, but not enough to affect range or management tasks such as cell balancing. “We probably will go down the route of two BMS units, because of the complexity of those extended looms,” Medwell says.

He adds that the BMS is also very important for getting the most range for the capacity and in thermal management, and believes there are better BMSs on the market,” he says. “There are many companies developing BMSs that are approaching 5% more efficiency than the OEM units, so it will be quite interesting when we come to do that. Someone might want to make a bespoke BMS for us, but it could also be an off-the-shelf system.

“Also, we have HV voltage cabling running the length of the cab and those extended BMS looms as well; we want to get rid of that, basically. In terms of cost, we are spending over £1000 per cab on connectors alone, so if we can take two to four of those away it would be a big saving.”

The battery capacity of 40 kWh gives the cab a range of about 120 miles in city traffic, which Medwell says meets the needs of most city taxi drivers. If a taxi driver lives in central London within its low-emissions zone, they will be driving between 50 and 80 miles in a day, he says, noting that most commute into the city from the vicinity of the M25 orbital motorway, which would bring daily mileages to between 100 and 120.

In London, that is enough most of the time, he reckons, while acknowledging that for some a 20-minute lunch stop at a fast charger might be required, which can add 40 or 50 miles. Talks with drivers outside London revealed daily mileages approaching 150 to 160, which would require 30-40 minutes on a fast charger.

Future capacity boost

However, the company commissioned some analysis to see how much capacity could be packed into the available volume. “We asked some battery specialists to look at the space in the cab and what sort of capacity we could create with the VDA 355 modules we are planning to use when we get into higher production volumes,” Medwell says.

“We can probably fit about 57 kWh in the present battery boxes. That is when we start to achieve ranges of 180 to 200 miles, which will be near-perfect for cab drivers.”

While the front battery box is in the taxi’s engine compartment, the other at the rear is in the boot. However, Medwell points out that luggage normally rides in the cabin with the passengers, while the boot is home to the spare wheel, a few tools and so. In the Clipper Cab, the spare wheel has therefore been moved to under the floor where the fuel tank used to be, and the use of VDA battery modules will allow the company to free up some extra space in the boot by reducing the height of the rear battery box.

That though is not a major concern. “It is not the ‘be all and end all’ for taxi drivers, as a lot of them don’t really use that rear space anyway,” Medwell says.

Finding space for components the vehicle manufacturer never intended to install is always a challenge in any conversion. But, says Medwell, “The benefit with things like the motors and inverters is that they are small compared to an engine. Where we have mounted the motor, it can sit really low down and quite far back. It is still in the front compartment, but it’s almost where the gearbox used to be.

“That just leaves the task of trying to find space to get as much battery capacity in as possible. It is always trickier when the car is not designed to be an EV, you don’t have all that space in the floor you get with a skateboard chassis.”

Repurposed heat exchangers

(Author’s photo)

Leaf batteries are passively air-cooled, so the Clipper Cab retains this system for its split pack. The rest of the thermal management system is also standard TX4 equipment, some of which is repurposed, and all the equipment is under the cab’s bonnet.

The main radiator for the diesel engine has been removed, but the smaller cooler for the now-absent automatic transmission is still in place and cools the onboard charger, the DC-DC converter, the motor and the inverter; the original condenser for the air conditioning also remains. Airflow over all these heat exchanges is aided by the cab’s original electrically driven cooling fan, providing plenty of spare capacity for hot days.

The 12 V battery that runs the cab’s original electrics is used to open and close the HV contactors in the main battery pack as well as running the TX4’s original electrics.

Nissan gearbox mods

Clipper also made a foray into mechanical engineering, modifying the Leaf’s direct drive gearbox used in place of the TX4’s large automatic transmission. Medwell explains, “Most EV retrofitters keep the car’s existing gearbox and connect the electric motor to it, but because the taxi had a huge automatic gearbox it would have been quite complicated to drive into that. So we decided to get rid of it and use the one from the Leaf.

That involved removing the differential from the gearbox, and cutting a hole in the casing so that the drive could be taken from the second of three cogs that provide the donor EV’s single gear ratio. A sealed sleeve takes the power into the original taxi propshaft, which drives the standard taxi differential through a CV joint.

Further, the gearbox has been turned through 90º to suit a rear-wheel-drive car, which also meant blanking off the output that originally sent drive to the Leaf’s left front wheel. One consequence of removing the differential and taking the drive from the second cog was that the Leaf’s electric motor and gearbox effectively run in reverse when the cab is moving forwards, and the original Nissan ECU limits the Leaf to 20 mph in reverse – one reason why Clipper developed its own ECU. “Basically, we can now change anything we like and go at any speed we want,” Medwell says.

While some gearboxes are not designed to run for prolonged periods or at high speeds in reverse, Clipper Automotive consulted with an expert who determined that the Leaf gearbox was more than enough durability.

The TX4 has a traditional and very sturdy steel ladder frame chassis on which the steel body is mounted. That makes the EV conversion process quite simple, Medwell explains, as the whole body can be unbolted and lifted off the chassis, and all the powertrain components that need to be replaced are attached to the chassis.

With the body off, Clipper Automotive takes the opportunity to inspect the chassis for corrosion, repair it if necessary and renew anti-corrosion treatments including stone-chip resistant paint. Replacing any worn items in the suspension, such as dampers, springs and bushings, is also much easier and quicker with the body removed.

Behind the wheel

Driving the Clipper Cab is very simple, and changes to the dash and controls are minimal. The TX4’s key is still used to turn the vehicle on, but the selector for the automatic transmission is gone, its place taken by a rotary selector from Zero EV with forward, reverse and neutral positions. Also, the fuel gauge has been replaced by a battery capacity gauge.

Driving on urban and suburban roads, the powertrain in its current state of tune is a little sluggish when moving off from a standing start, to the point of being a concern when joining a busy road even with the pedal to the floor. Medwell acknowledges that though, and says the company plans to address it through a small change to the ECU’s software.

“We have reduced the power output of the motor quite a lot, because range is a more important factor than 0-60 times,” he says. “We will tune it up a little because it is a bit slow off the line. It is quite punchy when you go from 20 to 30 mph, but 0-10 needs to be a bit quicker.”

Unlike many modern EVs, the Clipper Cab provides useful aural cues to its speed, as the powertrain whines at a pitch that rises with speed but not to the point of being intrusive.

Simple conversion

The simplicity of the conversion should make the process quick and therefore inexpensive. “The process will eventually be that the taxi driver comes in, gives us their diesel cab, and two days later drives out with an electric version,” Medwell says.

At the moment, that timescale is an aspiration, he admits, as there are delays in the supply chain. Building battery boxes and wiring looms in-house takes a couple of weeks, but once these are outsourced it will speed things up, he says.

Medwell adds though that the Nissan BMS is difficult to come by if the used pack doesn’t come with one, while worldwide demand for lithium-ion cells exceeds supply. Further, the approval process through the DVSA and the VCA takes about two weeks. “If we could start finding a way to fast track that it would help us get a cab in and out in under a week. That would be the aim.”

He says the first units will be run in a pilot scheme for a number of local authorities, and Clipper Automotive is now seeking investment to fund construction of the first 10-20 cabs for the scheme. It hopes to build these cabs in a single run this year.

“We will be renting the cabs initially, as that will let us keep an eye on them all,” he adds. “The rental price will match current the TX4 diesel rate, so the drivers can take the savings from fuel themselves. Sales will come later.”

Some key suppliers

HV connectors: Amphenol

Cabin heaters: DBK Group

ECU: JLCPCB

HV cabling: Fellten

Gear selection: Fellten

Battery boxes: In house

ONLINE PARTNERS